via Today’s iPhone

If you don’t already know, Flappy Bird is the hot new mobile game right now. The premise is simple: navigate the bird through the gaps between the green pipes. Tapping the screen gives a slight upward impulse to the bird. Stop tapping and the bird plummets to the ground. Timing and reflexes are the key to Flappy Bird success.

This game is HARD. It took me at least 10 minutes before I even made it past the first pair of pipes. And it’s not just me who finds the game difficult. Other folks have taken to Twitter to complain about Flappy Bird. They say the game is so difficult, that the physics must be WRONG.

https://twitter.com/NurulAkiller/status/428892206754037760

https://twitter.com/MadsEltonNilsen/status/428794101899616256

https://twitter.com/ThatPuckBeaut/status/428781313433149440

https://twitter.com/garyscott_/status/428763347794665472

https://twitter.com/La_Tayy/status/428689724425785344

https://twitter.com/Bella_Bonita_/status/428680939326017536

https://twitter.com/maaddawwg/status/427833802140815361

https://twitter.com/184bader/status/428541838283116544

https://twitter.com/ImChase_WutIDK/status/428532979192049664

https://twitter.com/veeedoh/status/428419628600410112

So, is the physics unrealistic in Flappy Bird?

Sounds like a job for Logger Pro video analysis! I used my phone to take a video of Flappy Bird on my iPad. To keep the phone steady, I placed it on top of a ring stand with the iPad underneath.

(I’ve uploaded several of the videos here if you’d like to use them yourself or with students: Flappy Bird Videos.)

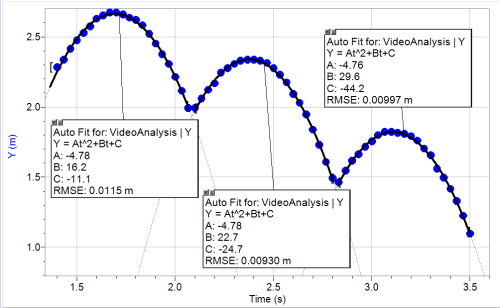

Then I imported the videos into Logger Pro and did a typical video analysis by tracking Flappy’s vertical position in the video. Sure enough, the upside-down parabolic curves indicate Flappy is undergoing downward acceleration.

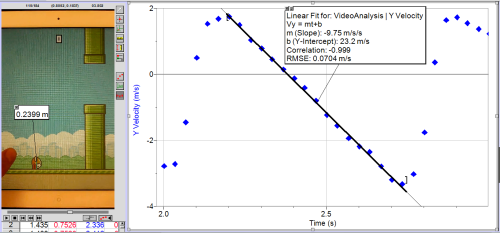

But do the numerical values represent normal Earth-like gravity or insanely hard Jupiter gravity? In order to do this, we need to (1) set a scale in the video so that Logger Pro knows how big each pixel is in real life and (2) determine the slope of Flappy’s velocity-time graph while in free fall, which is equal to the gravitational acceleration.

The only thing we could realistically assume is the size of Flappy Bird. If we assume he’s as long as a robin (24 cm), then the slope of the velocity-time graph is 9.75 m/s/s, which is really close to Earth’s gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s/s. Flappy Bird is REAL LIFE.

So then why is everyone complaining that the game is unrealistic when, in fact, it is very realistic? I blame Angry Birds and lots of other video games. Repeating the same video analysis on Angry Birds and assuming the red bird is the size of a robin (24 cm), we get a gravitational acceleration of 2.5 m/s/s, which only 25% of Earth’s gravitational pull.

In order to make Angry Birds more fun to play, the programmers had to make the physics less realistic. People have gotten used to it, and when a game like Flappy Bird comes along with realistic physics, people exclaim that it must be wrong. As one of my students notes:

UPDATE 31 Jan 2014:

Inspired by a tweet from John Burk,

we made a video showing Flappy Bird falling at the same rate as a basketball:

Here’s what I did: We determined from the analysis above that Flappy Bird is about 24 cm across. Conveniently, basketballs are also about 24 cm across. So I had my physics teacher colleague Dan Longhurst drop a basketball so I could video it with my iPad. Dan just needed to be the right distance away from the camera so that the size of the basketball on the iPad screen was the same size as Flappy Bird on the screen (1.5 cm). Next, I played the basketball drop video and Flappy Bird on side-by-side iPads and recorded that with my phone’s camera. Once I got the timing right, I uploaded the video to YouTube, trimmed it, made a slow motion version in YouTube editor, then stitched the real-time and slow motion videos together to create the final video you see above.

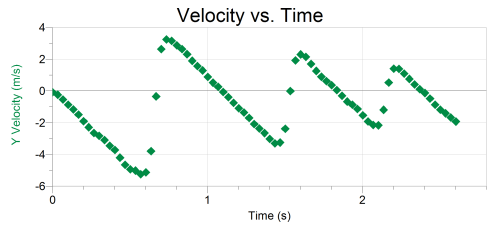

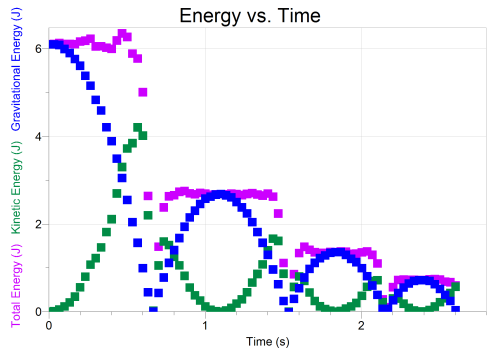

UPDATE 1 Feb 2014: While the gravitational acceleration in Flappy Bird is realistic, the impulse provided by the taps are NOT realistic. Here’s a velocity-time graph showing many taps. When a tap happens, the velocity graph rises upward:

As you can see, no matter what the pre-tap velocity (the velocity right before the graph rises up), the post-tap velocity is always the same (a bit more than 2 m/s on this scale). This means that the impulses are not constant. In real life, the taps should produce equal impulses, which means that we would see that the differences between pre- and post-tap velocities are constant.

TL;DR: Is the physics in Flappy Bird realistic? Yes AND no.

YES: The gravitational pull is constant, producing a constant downward acceleration of 9.8 m/s/s (if we scale the bird to the size of a robin).

NO: The impulse provided by each tap is variable in order to produce the same post-tap velocity. In real life, the impulse from each tap would be constant and produce the same change in velocity.

UPDATE 1 Feb 2014 (2): Fellow physics teacher Jared Keester did his own independent analysis and shares his findings in this video: